As people will know, Sara Sharif was brutally murdered by her father and stepmother in August 2023 and they were recently convicted of that offence. As part of the factual background of the case, it emerged that Sara together with her siblings had been the subject of Family Court proceedings and that decisions had been made in those proceedings which, had they potentially gone a different way, Sara would not have been in the family setting she was in before her murder.

Journalists understandably wanted to report on this aspect of the case and applications were made for them to be able to report on the Family Court proceedings. A decision was taken about what could be reported and what could not, and one of the issues that was restricted was identification of the Judges who had taken decisions about Sara and her siblings.

The case went before Williams J https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Fam/2024/3330.html who upheld the decision that the identity of the Judges should not be disclosed.

I accept that there is now considerable force – indeed compelling weight – behind the submissions as Mr Barnes puts it extracted below. That is not to say that all that he submits is correct or that I necessarily agree with it, but the questions posed are legitimate ones which justify exploration by the press.

(a) The criminal trial has served to crystallise an overwhelming public interest in understanding: (i) how Sara came to be placed in the care of her father, (ii) the effectiveness of the safeguarding undertaken by the Family Court, local authority, and CAFCASS, and (iii) the local authority’s understanding of the risk posed by the father from its lengthy involvement with the family1 in light of the referral made by Sara’s school on 10th March 2023 in relation to which the local authority made a decision to take no further action by 16th March 2023; b. The “unbroken chain of causation” back to the family proceedings in 2013, 2015/6, and 2019 is now very clearly established.(c) c. The school referral in March 2023 was referred to within the criminal trial and reported, as was the fact of an order being made by the Guildford Family Court in 2019…..

From the point of view of a judge who has practised in family law for 35 years and sat as a judge for 9 years including 4 years as the Family Presiding Judge for the South Eastern Circuit (which includes Surrey) my perspective on the investigations which took place, the assessments which emerged, the recommendations which were made and the decisions which were taken by the family court in 2013, 2015 and 2019 appear to be well within the boundaries of what one would typically encounter in a case of this nature.

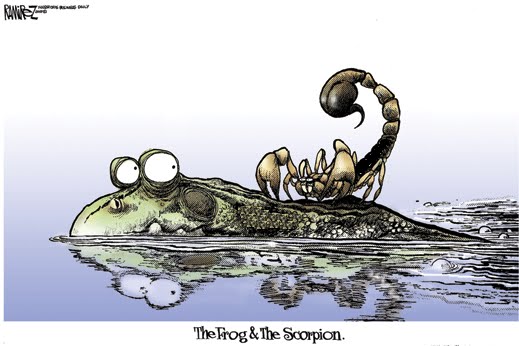

However, it is perhaps precisely that perspective and the subsequent shocking murder of Sara which illustrates why there is a compelling public interest in the media being able to undertake their own consideration of the material and to question or test how we approached the issues and to ask the legitimate question of whether there were things that the system could have done differently or better. Nothing can bring Sara back, nothing can undo the harm that must inevitably have been done to her siblings from their exposure to what appears to have been sadistic long-term torture of her. The sentencing judge described it in all its appalling detail. There will be other processes which will examine the responses of the system but those other avenues do not in any way undermine the compelling public interest in the media being able to discuss the history of Sara’s involvement with the child protection system including the courts from the moment of her birth until her tragic death. If that discussion highlights shortcomings in what was done and whether Sara might have been better protected then those are issues which those of us in the family justice system will have to listen to and consider, those in children’s services will and those who have control of the resources made available to the Family Justice System and to child protection services and safeguarding generally will need to reflect upon and consider whether we can and should do anything differently and whether more resources in terms of child safeguarding and protection or within the Family Justice System are required to minimise the risk of this happening again. On the other hand, that exploration and discussion by the media may only reveal that parents who are sufficiently determined and manipulative can thwart the system.

In part of that judgment, Williams J was somewhat critical about the proposition that the Court should proceed on the basis that any reporting would be responsible, fair and accurate :-

The media submit that authority supports the proposition that the Court must proceed on the footing that any reporting of the proceedings will be responsible, fair and accurate (R v Sarker [2018] 1 WLR 6023at [32(iii)(b)]). That may be a useful starting point, but experience regrettably shows that some reporting is better than others and that it is not a reliable end point. It is also the case that once the media applicants have published the information it is available to anyone to do with it as they wish and in an age of disinformation and anti-fact the court must have an eye to what onward use may be made of the information. As the reporting of the murders of Alice da Silva Aguiar, Bebe King and Elsie Dot Stancombe demonstrates all too clearly, those with malign intent can rapidly distort information to meet their own purposes with devastating real-world consequences. As I said in the course of the hearing the reality is that there will be a spectrum of reporting – even within the represented media parties. Many will indeed report matters responsibly, fairly and accurately. Some will not. Contrast the extract of a judgment and a headline in a well-known national daily newspaper reporting it.

Extract

What this case is not about though is whether an Islamic marriage ceremony (a Nikah) should be treated as creating a valid marriage in English law.

Headline

A British court has recognised sharia law for the first time in a landmark decision as a judge ruled that a wife can claim her husband’s assets in the split. The High Court ruling on Wednesday said their union should be valid and recognised because their vows had similar expectations of a British marriage contract.

On Friday 13th December 2024 I responded to an application for permission to appeal made on behalf of Ms Tickle and Ms Summers and adjourned the application pending this judgment giving reasons for doing so. On Saturday 14th December at 19.18 GMT the Guardian carried a story written by Ms Tickle and Ms Summers reporting that I had refused permission to appeal. Accurate – no; fair – no; responsible – I would venture to suggest not. I could make several observations about how fairly, responsibly and accurately the Dispatches programme broadcast on 20th July 2021 depicted a number of decisions of the family courts. Thank goodness that journalists don’t have to operate as the courts do and hear both sides before delivering their verdict! Is reporting which only presents one side of the story fair, responsible and accurate? By any ordinary meaning of those words, I would suggest not. What it is very close to is advocacy or campaigning and that is one aspect of reporting but so is sensationalism as well as good investigative reporting. To apply some broad presumption which equates the sort of reporting undertaken by Nick Wallis to that of Andy Coulson is simply wrong. The Leveson Inquiry and the imprisonment of members of the press for egregious infringements of the Article 8 rights of hundreds of individuals makes abundantly clear that some elements of the media do not always adhere to high standards. So with respect it seems to me that to create an assumption that the press reporting will be fair, accurate and responsible is to create the equivalent of the Emperor’s New Clothes narrative which everyone knows is false, but no one dare state. Many of the media no doubt will adhere to that standard but regrettably experience of the real world as opposed to some utopian ideal teaches us that some will not – including amongst the mainstream media. Authorising disclosure to the press of extensive material about sensitive shielded justice proceedings and permitting reporting on it does not mean they will all report it fairly, accurately, and responsibly and the more extensive the disclosure and publication authorised the more the court is entitled to balance that with minimising the risks of disproportionate infringements of Article 8 rights of those concerned.

My conclusion on the naming of third parties and judiciary is therefore that there is no presumption that they should be named in shielded justice cases. For the judiciary I would accept that there is an assumption in shielded justice cases of naming because s.12 Administration of Justice Act 1960 contemplates that their name will be open notwithstanding the presence of the broader shield. In relation to other third parties – social workers and other child protection professionals – I would be inclined to a starting point that shielded justice preserves anonymity for them. For experts, jurisprudence and the Reporting Pilot provide a starting point of identification.

But these starting points must always be subject to a case specific evaluation which will involve consideration of elements relating to the case itself, the individuals and what it is legitimate to infer from the accumulation of knowledge we have about risks arising in the same way we may infer risk to children arising from publication and risks to health professionals in contentious medical treatment cases like Charlie Gard and Zainab Abassi.

I don’t think it will surprise anyone to know that the Press disagreed with that categorisation and that the Williams J decision was appealed.

Here’s the link to the appeal judgment

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2025/42.html

Tickle & Anor v The BBC & Ors [2025] EWCA Civ 42 (24 January 2025)

(For what my own personal opinion is worth – very little – but I’ll set it out, I do think that if the Courts are going to name social workers and Local Authorities and paediatricians, then in circumstances where there is legitimate media interest in decisions made by Judges then they too should be named. I slightly share Williams J concerns that the information might not be used to provide a balanced and reasonable account – we do after all live in an era when a national newspaper runs a headline of “Enemies of the people” to describe a Supreme Court ruling that they disagreed with… but I also think that the Streisand Effect is real and the more one tries to keep the Press away from something the more tenacious they’re likely to be. A tough case but on balance I would have published the names)

Anyway, here are the grounds for the appeal

The journalists’ grounds of appeal (upon which the Media Parties also rely) take four main points:

i) It was a serious procedural irregularity for the judge not to have given reasons before anonymising the historic judges.

ii) The judge adopted an unfair, biased and inappropriate approach to the journalists and the media generally (including relying on his own erroneous analysis of alleged media irresponsibility), thereby unacceptably encroaching on their rights under article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). This ground was added by amendment and permission has not yet been granted to allow it to be pursued.

iii) The judge ought to have held that the demands of open justice meant that anonymity for a judge could not be justified within the framework of balancing article 8 and article 10 of the ECHR.

iv) The part of the Order anonymising the historic judges could not be justified in the absence of any specific application or evidential foundation, and was inimical to the proper administration of justice.

The Judges in question were approached for their views:-

On 20 December 2024, King LJ directed that the historic judges be contacted to obtain their views (if they wished to express any). On 9 January 2025, leading and junior counsel for the historic judges filed a note indicating that: (a) none of them had sought anonymity, (b) each of them now had serious concerns about the risks which would arise if they were now identified, particularly in the prevailing circumstances, including the content and often inflammatory nature of public and media commentary arising from the intense scrutiny which has followed from the December judgment, (c) those concerns related not only to their own personal wellbeing but also to their family members and others close to them, whose interests the court might also want to take into account, (d) two of the historic judges (Judges 1 and 2, who were now retired and made only an emergency protection order and an interim care order respectively) considered that it would be right for their identities to remain protected, (e) Judge 3 was a sitting judge who was not, therefore, able to adduce evidence and did not feel it appropriate to express a position on whether their identity should remain protected, and (f) the historic judges considered that a risk assessment should be undertaken before any decision was made and that, if the anonymity part of the Order were to be varied, further assessments should be made of what (if any) protective measures should be taken before that decision was implemented, and (g) the Head of Security at HMCTS’s Chief Financial Officer’s Directorate had said that the Judges: “do not have secure digital footprints and the ease at which the residential address details of the judges can be accessed by anybody utilising the internet, creates very significant security/safety vulnerabilities. If there is a campaign, including potential ‘hate’ messages targeting [the historic judges], their personal safety and the personal safety of their family could be very severely affected”.

(I think that this is powerful – as we know, there is a very polarised media and once things appear in the media they also have a life of their own on social media and that can become very ugly very quickly. One can easily forsee some people reading an assertive headline and taking it upon themselves to harass the Judges. We can’t forget that the people to blame for Sara’s murder are the people who were convicted of it. And also, that Judges understandably are currently very mindful of an extremely serious assault that took place on a Judge in Milton Keynes, despite that being in a Court building with security)

The first question the Court of Appeal addressed was whether there was jurisdiction to prohibit the identification of the Judges.

Issue 1: Was there jurisdiction to prohibit the publication of the names of judges?

The critical jurisdictional question is the one that, it seems to me, the judge ought to have asked himself when it came into his head to order anonymity for the historic judges at the end of the hearing on 9 December 2024. At that point, no party had suggested that such anonymity was necessary. Moreover, no evidence of any kind had been filed supporting the making of such an order. The position at that date was, notionally at least, that the names of the historic judges had been in the public domain since the hearings over which they presided years before. It is true that the cases before them would have been heard in private and covered by section 12 of the AJA 1960 and section 97, and would, in all likelihood have been listed as something like “Re S (children)”. But the historic judges’ names appeared on each of the orders that they made. Orders are public documents. Further, the fact that these judges were sitting on the days in question at the courts in question was public knowledge as it should have been. In these circumstances, once the matter occurred to the judge, he ought, in my view, to have asked himself on what legal basis he could order the anonymity of the historic judges.

Neither the Local Authority nor the Guardian had submitted to the judge at any stage that the protection of the children required that the historic judges be granted anonymity. That remains the position. Accordingly, the parens patriae inherent jurisdiction of the court to protect the children was not engaged. Whilst there was no application for an injunction under section 37, the court would, in theory, have had power to grant an injunction to restrain the publication of the historic judges’ names (see the wide scope of that section as explained by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Convoy Collateral Ltd v. Broad Idea International Ltd [2021] UKPC 24, [2023] AC 389 at [57], and by the UKSC in Wolverhampton City Council v. London Gypsies and Travellers [2023] UKSC 47, [2024] AC 983 at [145]-[153]). It would have been very unusual for the court to grant such an injunction of its own motion without any application being made or intimated by the historic judges or anyone else. In any event, it has not really been suggested by anyone that section 37 (without section 6) gave the judge the jurisdiction to order anonymity. For the avoidance of doubt, no cause of action, whether in misuse of private information, breach of confidence or anything else was being asserted before the judge.

It seems to me, therefore, that the only realistic jurisdictional foundation for the judge’s decision was section 6 of the HRA 1998, perhaps taken alongside section 37. Section 6 provides, as I have said, that it is “unlawful for a public authority to act in a way which is incompatible with” an ECHR right. Accordingly, if the judge had, on the 9 December 2024, reason to believe that the historic judges’ article 2 or 3 rights would or might be engaged by allowing the press to publicise their names, he would have had to refrain from doing that, and if he had had reason to suppose that their article 8 rights would be engaged, he would have had to undertake the balancing exercise envisaged in Re S.

It is clear, in my judgment, that articles 2, 3 and 8 apply as much to judges as to any other person. It is less clear, however, that judges, even in cases like this, need to consider, of their own motion, when asked to relax reporting restrictions, whether to anonymise the names of the judges who have heard the cases in question. I have considered very carefully the submissions of the advocate to the court to the effect that the rare and extreme factual background to this case might itself mean that the article 8 threshold for the judges had been reached. I have looked carefully at the judge’s later reasoning that explains why he thought that social media and reporting risks to judges have, in the modern world, became sufficiently alarming and serious to reach the threshold.

I have, however, concluded that the judge was wrong. He had no jurisdictional foundation for making the anonymity order he did. Section 6 did not require him to trawl through his own experience to see if there were risks that he could imagine facing the historic judges. If, notwithstanding the lack of evidence to that effect, the judge was concerned about their being named, there were other, more appropriate, ways to protect them. He could have contacted HMCTS to warn them of the Order that he was making and the risks that he foresaw. HMCTS would, in that event, as has happened now, have considered how the judges could be protected.

I should interpose that nothing I say here should be interpreted as minimising the risks that judges in the position of the historic judges face. I have taken very seriously what the historic judges and HMCTS have said. But none of that material, which substantially relates to the potential impact on the judges of the publicity generated following the making of the Order, was before the judge. He had no evidential basis on which to think that the threshold for the application of articles 2, 3 or 8 had been reached.

It is the role of the judge to sit in public and, even if sitting in private, to be identified, as explained in Scott v. Scott, Felixstowe and Marsden. Judges will sit on many types of case in which feelings run high, and where there may be risks to their personal safety. I have in mind cases involving national security, criminal gangs and terrorism. It is up to the authorities with responsibility for the courts to put appropriate measures in place to meet these risks, depending on the situation presented by any particular case. The first port of call is not, and cannot properly be, the anonymisation of the judge’s name. That must be particularly so, where those names are already notionally in the public domain. Moreover, it is no answer as was suggested, to say that there is only a limited interference with open justice, because the historic judges’ names add little to the story. For all the reasons given in the cases I have cited, it is not for judges to decide what the press should report or how journalists should do their jobs.

The authorities that I have cited demonstrate that judges are in a special position as regards open justice. The integrity of the justice system depends on the judge sitting in public and being named, even if they sit in private. The justice system cannot otherwise be fully transparent and open to appropriate scrutiny.

For the avoidance of doubt, I am not saying that judges are obliged to tolerate any form of abuse or threats (see [54] above). Nor am I saying that it would never be possible for section 6 of the HRA to allow, or even require, a court to consider, even conceivably of its own motion, making an anonymisation order relating to judges. In my judgment, however, it is very hard to imagine how such a situation could occur. That is for three reasons. First it is difficult to see that such an order could be justified without specific compelling evidence being available as to the risks to the judges in question. Secondly, the court would have to be satisfied that those risks could not be adequately addressed by other security measures. Thirdly, the court would have to conclude that the risks were so grave that, exceptionally, they provided a justification for overriding the fundamental principle of open justice.

The first reason is sufficient to dispose of the anonymisation of the historic judges in the Order in this case. There was no evidence before the judge on 9 December 2024 that the judges had been physically threatened, and none supporting the proposition that their article 8 rights were in jeopardy. The judge had no evidence about the historic judges’ private or family life, and did not need to speculate as to the generic risks that family judges might face in the modern age of social media. I agree with what Nicklin J said in the IPSA case (see [47] above) about the threshold that needs to be reached and the need for resilience. I acknowledge that the case of Spadijer recognises the changes that have occurred in our societies and the increased sensitivity of our era, but I do not think that affects the need for judges to operate in the open.

In these circumstances, I take the clear view that the judge had no basis, in the absence of specific evidence affecting the historic judges, on 9 December 2024, to think that articles 2, 3 or 8 were or might be engaged. He, therefore, had no need to undertake any balancing exercise between article 8 and article 10. The historic judges’ identities were in the public domain and ought to have remained in the public domain.

We do not know whether the judge ever became aware of the fact that abusive threats against the historic judges have, since the verdicts against the father and step-mother, most regrettably appeared on the internet in social media posts. The father’s counsel obtained a sample of these threats and sought to admit them in evidence on the appeals. We looked at them de bene esse (for what they were worth). I would admit them in evidence, since they were not available before the hearing on 9 December 2024, and it was useful for the court to know about them in its deliberations. To my mind, however, these threats do not alter the position. They are not threats from parties affected by the orders that the historic judges made. They are generic threats of the kind that are, unfortunately, all too commonly now made against politicians and public figures of all kinds. It is one thing for an internet troll to post a message saying that “politician X should be strung up”, and quite another for a party to litigation to threaten the judge directly. Likewise, the generic fears of the historic judges and the recently expressed concerns of HMCTS do not, in my judgment, alter the position. There are, as I have said, other ways of protecting the historic judges.

In the circumstances of this case, the judge had no jurisdiction to anonymise the historic judges either on 9 December 2024 or thereafter. He was wrong to do so, and the Order must be varied accordingly. I will return to the process by which that is to be achieved in the final section of this judgment.

To be honest, having succeeded on that point the appeal is inevitably going to succeed, but we’ll keep going.

Issue 3: Was there inappropriate bias against or unfairness towards the media?

I have set out some of the colourful language used by the judge at [27] and [30]-[33]. It is said that the judge demonstrated unfairness and bias against the media in general and the journalists in particular. This ground is also academic now that I have decided that the judge had no jurisdiction to do as he did.

I do, however, think that the threshold for permission to appeal on this ground is met, and I would accordingly give that permission on the basis that the ground had a real prospect of success. It was, I think, unfair of the judge to say, with such vehemence, at [60] that the journalists had been guilty of inaccurate, unfair and irresponsible reporting. The decision to adjourn the journalists’ application for permission to appeal just before the end of term was akin to dismissing the application. The distinction was, in the circumstances, a technical one. The decision to adjourn necessitated the application to me for permission to appeal, which I granted on 19 December 2024. At the time that the judge adjourned the application for permission to appeal on 13 December 2024, the parties thought, as the judge had told them, that his reasons would not be available until the New Year. It was excessive in the circumstances to accuse the journalists of irresponsible reporting even if the application for permission had been technically adjourned rather than dismissed. His sarcastic remark at [60] about the Channel 4’s Dispatches programme of 20 July 2021 was unwarranted. He said, for no reason that I could discern: “[t]hank goodness that journalists don’t have to operate as the courts do and hear both sides before delivering their verdict!”. Such sarcasm has no proper place in a court judgment.

There are other examples in the judgment of the judge taking an excessively strong line about the quality of reporting in other cases. It was inappropriate for him to have prayed in aid other cases within his experience (as, for example at [59]) to support the position he had adopted without any of the parties asking him to do so.

I do not intend to proliferate my remarks. The mistake the judge made was to think that he could properly trawl through his own experiences to create a case for anonymising the judges. He should not have done so. Courts operate on the basis of the law and the evidence, not on the basis of judicial speculation and anecdote, even if it is legitimate to take judicial notice of some matters. In short, the judge’s judgment demonstrates, to put the matter moderately, that he got carried away.

It is not necessary to decide whether the judge’s inappropriate and unfair remarks about the press and the journalists amounted to actual or apparent bias. He undoubtedly behaved unfairly towards the journalists and Channel 4 – and that is enough to allow the appeals. The judge lost sight of the importance of press scrutiny to the integrity of the justice system. The case should be remitted for further hearings to a different Family Division judge.

The Court of Appeal determined that the names of the Judges would be provided to the Press but that they would be given 7 days so that His Majesty’s Court Service could have time to prepare any necessary additional security measures

For the reasons I have given, I would allow the appeals primarily on the jurisdiction ground, but also on the grounds of the judge’s failure to seek submissions or evidence before giving his decision, and his unfair treatment of the journalists and Channel 4. I would, as I have said, give all the media parties permission to raise the additional ground of appeal. I would deprecate the judge’s use of anecdotal material and his own experiences to create a case for anonymising the judges.

The historic judges have asked for time to prepare themselves if their names are to be revealed. Since that is the result of allowing the appeal, I would order that they be given 7 days from the date of this judgment before their names are published, to allow HMCTS to put measures in place to protect them from any potential harm once their names are released.