(or trois, really)

This is a High Court case involving hair strand testing, where three different companies were involved and produced three slightly different results. The science is discussed and some guidance for more meaningful and clearer reports is provided.

Note that this case is NOT authority for “one of these companies is the bestest” or “one of these companies is the suck” – it is notable that each of the three companies ended up lawyering up for the hearing, two of them silking up.

There’s a lot at stake with revenue and commercial reputation here for each of these companies and I’m not going to be damn foolish enough to draw any conclusions of my own, so I’ll stick to what the Court said.

Re H (A Child :Hair Strand Testing) 2017

http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWFC/HCJ/2017/64.html

The case was heard by Mr Justice Peter Jackson (I think it might be his last case as plain J. For the moment, he is LJ. Frankly, if and when our current Dali Lama moves on, I have my own views about a suitable replacement.)

3. The reason why this hearing has involved five days of evidence is because there is also an underlying factual issue. Has the mother been using drugs, albeit at a low level, during the past two years? She adamantly denies doing so and, with one significant exception, the other evidence supports her. The exception is a body of scientific information from hair strand tests taken over the two-year period, which are interpreted by the testing organisations as showing low-level cocaine use for at least some of the time. That has been challenged by the mother and I have heard from five expert witnesses: one from each of the three testing organisations, one on behalf of the mother, and one jointly instructed.

From my reading of the case, by the time of the final hearing, it was common ground that the child should be placed with the mother (although that only became common ground 2 days before the final hearing) and the only issue was whether that should be under a Care Order or a Supervision Order – so in this particular case, the outcome of the hearing was not hinging on the outcome of the drug tests, but there are of course many others where it does, so the good practice guidance is going to be helpful for those.

In summary, there is no doubt that the mother was in a dismal state two years ago, to the point where she was quite incapable of looking after any child. It is now accepted that she has turned her life around to the point that she is now capable of looking after one child with support. She says that she has achieved this by avoiding damaging relationships and by complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol. The local authority argues that the hair strand testing shows that complete abstinence has not been achieved, which raises the level of risk that Holly will get caught up in future drug use of the kind seen in the past. It also argues that the hair strand tests show that the mother has not been telling the truth and consequently that she cannot be fully trusted.

There were in all some 47 hair strand tests in this case. That’s not a typo. Forty. Seven. Forty-seven. 47. There was some variation in the tests, even when they were taken at similar times.

37. In relation to the variability of results, the tables provided by Mr Poulton at [C164z-164ac] illustrate that the range of results obtained by the different laboratories varies quite considerably. Notably, the DNA Legal results for 2016 were in some cases two or three times higher than those found by the other organisations. This is then reflected in the fact that DNA Legal reported findings in the low to medium range, while the others reported only low findings. However, direct comparison between the test results is to some extent confounded by the fact that hair was taken at different times, and that the assumed 1 cm growth rate may not be correct. It is also important to remember that the results may be affected by differences in laboratory equipment and differences in the way the hair is washed before analysis.

38. The testing carried out in July 2017, allows for the most direct comparison as the hair was all harvested at the same time. Even so, as an example of variability, two laboratories showed a cocaine result relating to the month of April at 0.11 and 0.17 (well below the cut-off), while the third showed it as 0.52 (just above the cut-off).

You can see that this is problematic. Courts, and social workers, and lawyers and parents need to know that when a hair strand test says that someone has taken cocaine (or hasn’t), that the test is accurate. Here, if a parent had done just one of those three tests on their own, a conclusion could have been drawn that they were clean, or that they had used cocaine depending on nothing more than which company did the test. That can’t be right.

And it doesn’t mean that one company is being too harsh, or that another is messing it up, it is just illustrative that there are limits, presently, to the science.

[I have already seen this morning triumphant press releases trumpeting that this High Court Judge has praised x company to the skies. I think that somewhat overstates things. That’s just my personal opinion, naturally. The Judge does clearly prefer, in this case, the evidence from the companies to that of the independent expert who was attacking their methodology, but it would be simplistic, in my view, to claim that the judgment strongly backs the science or an individual company or sets down a marker that hair strand test results are definitive always]

Yes, Cousin It, your hair strand test has come back positive for Creepy, Spooky and altogether Oooky.

The Judge says this :-

40. In my view, the variability of findings from hair strand testing does not call into question the underlying science, but underlines the need to treat numerical data with proper caution. The extraction of chemicals from a solid matrix such as human hair is inevitably accompanied by margins of variability. No doubt our understanding will increase with developments in science but, as matters stand, the evidence in this case satisfies me that these testing organisations approach their task conscientiously. Also, as previous decisions remind us, a test result is only part of the evidence. A very high result may amount to compelling evidence, but in the lower range numerical information must be set alongside evidence of other kinds. Once this is appreciated, the significance of variability between one low figure and another falls into perspective

41. I must say something about the reporting of test results as being within the high/medium/low range. In fairness to the testing organisations, this practice has developed at the request of clients wishing to understand the results more easily. The danger is that the report is too easily taken to be conclusive proof of high/medium/low use, when in fact the actual level of use may be lower or higher than the description. You cannot read back from the result to the suspected use. Two people can consume the same amount of cocaine and give quite different test results. Two people can give the same test result and have consumed quite different amounts of cocaine. This is the consequence of physiology: there are variables in relation to hair colour, race, hair condition (bleaching and straightening damages hair), pregnancy and body size. Then there are the variables inherent in the testing process. Dr McKinnon explained that there is therefore only a broad correlation between the test results and the conclusions that can be drawn about likely use and that it should be recognised that in some cases (of which this is in his opinion, one) there will be scope for reasonable disagreement between experts.

42. Furthermore, the evidence in this case shows that even as between leading testing organisations, the descriptions are applied to different numerical values. DNA adopts the figures set out in the relevant studies, while the two other organisations divide their own historic positive laboratory results into thirds (Alere) or use the interquartile range for medium (Lextox).

43. So it can be seen that there is variability in descriptions that are intended only to assist. As a case in point, the DNA Legal high figure for 2016 (1.50), which was itself significantly higher than that reported by the other testers, would only be described as falling into the medium range by two of the three organisations.

(Again, that’s not to say that one company is better than the others, or that one is getting it wrong, but you can see that a helpful label of high, medium or low use, is only helpful if you know what high, medium or low means FOR THAT company. It won’t necessarily be the same as for another company)

Hair strand testing has been considered in several previous cases:

In Re F (Children)(DNA Evidence) [2008] 1 FLR 328, a case involving DNA testing, Mr Anthony Hayden QC said this, amongst other things, at paragraph 32:

“The reports prepared for the court by the… experts should bear in mind that they are addressing lay people. The report should strive to interpret their analysis in clear language. While it will usually be necessary to recite the tests undertaken and the likely ratios derived from them, care should be given to explain those results within the context of their identified conclusions.”

In London Borough of Richmond v B [2010] EWHC 2903 (Fam), a case about hair strand testing for alcohol, Moylan J said this at paragraph 10, referring to the practice direction that became PD12B:

“10. I have referred to the Practice Direction because some of the expert evidence which has been produced in this case appears to have been treated as though it was not expert evidence. It may well be that results obtained from chemical analysis are such as to constitute, essentially, factual rather than opinion evidence because they are not open to evaluative interpretation and opinion. Although I would add that it is common for such analysis to have margins of reliability. However, the Practice Direction applies to all expert evidence and it will be rare that the results themselves are not used and interpreted for the purposes of expert opinion evidence.”

And further, at paragraph 22:

“When used, hair tests should be used only as part of the evidential picture. Of course, at the very high levels which can be found (multiples of the agreed cut off levels) such results might form a significant part of the evidential picture. Subject to this however, both Professor Pragst and Mr O’Sullivan agreed that “You cannot put everything on the hair test”; in other words that the tests should not be used to reach evidential conclusions by themselves in isolation of other evidence. I sensed considerable unease on the part of Professor Pragst at the prospect of the results of the tests being used, other than merely as one part of the evidence, to justify significant child care decisions;”

Bristol City Council v The Mother and others [2012] EWHC 2548 (Fam), Baker J was concerned with testing for cocaine and opiates. In that case, an unidentified human error in the process led to a false positive report. At paragraph 25, Baker J endorsed these four propositions:

“(1) The science involved in hair strand testing for drug use is now well-established and not controversial.

(2) A positive identification of a drug at a quantity above the cut-off level is reliable as evidence[1] that the donor has been exposed to the drug in question.

(3) Sequential testing of sections is a good guide to the pattern of use revealed.

(4) The quantity of drug in any given section is not proof of the quantity actually used in that period but is a good guide to the relative level of use (low, medium, high) over time.”

Baker J declined to go further, saying this at paragraph 25:

“The jurisdiction of the family courts is to determine specific disputes about specific families. It is not to conduct general inquiries into general issues. Occasionally, a specific case may demonstrate the need for general guidance, but the court must be circumspect about giving it, confining itself to instances where it is satisfied that the circumstances genuinely warrant the need for such guidance and, importantly, that is fully briefed and equipped to provide it.”

Most recently, Hayden J returned to the subject in London Borough of Islington v M & R [2017] EWHC 364 (Fam), a case of hair strand testing for drugs. He said this at paragraph 32:

“It is particularly important to emphasise that each of the three experts in this case confirmed that hair strand testing should never be regarded as determinative or conclusive. They agree, as do I, that expert evidence must be placed within the context of the broader picture, which includes e.g. social work evidence; medical reports; the evaluation of the donor’s reliability in her account etc. These are all ultimately matters for the Judge to evaluate.”

Peter Jackson J (as he then was) drew up 12 principles about hair strand testing (they are really useful). I hadn’t myself been aware of the principle that some hairs in a sample at any time won’t actually be growing (resting hairs – about 15%) which is why you can’t just test on a single hair, you need a large enough sample to make sure that you’ve accounted for hairs within the sample where there will not have been any growth. If you just tested one hair, that hair might be a resting growth hair, and would thus show you cocaine use from 4-6 months ago and fool you into thinking that it is a growing hair where that would mean recent cocaine use.

28. I next set out twelve propositions agreed between the expert witnesses from whom I have heard:

(1) Normal hair growth comprises a cycle of three stages: active growing (anagen), transition (catagen) and resting (telogen). In the telogen stage can remain on the scalp for 3-4 (or even 5 or 6) months before being shed. Approximately 15% of hair is not actively growing; this percentage can decrease during pregnancy.

(2) Human head hair grows at a relatively constant rate, ranging as between individuals from 0.6 cm (or, in extreme cases, as low as 0.5 cm) to 1.4 cm (or, in extreme cases, up to 2.2 cm) per month. If the donor has a growth rate significantly quicker or slower than this, there is scope both for inaccuracy in the approximate dates attributed to each 1 cm sample and for confusion if overlaying supposedly corresponding samples harvested significant periods apart.

(3) The hair follicle is located approximately 3-5 mm beneath the surface of the skin; hence it takes approximately 5-7 days the growing hair to appear above the scalp and can take approximately 2-3 weeks to have grown sufficiently to be included in a cut hair sample.

(4) After a drug enters the human body, it is metabolised into its derivative metabolites. The parent drug and the metabolites are present in the bloodstream, in sebaceous secretions and in sweat. These are thought to be three mechanisms whereby drugs and their metabolites are incorporated into human scalp.

(5) The fact that a portion of the hair is in a telogen stage means that even after achieving abstinence, a donor’s hair may continue to test positive for drugs and/or their metabolites for a 3-6 month period thereafter.

(6) Hair can become externally contaminated (e.g. through passive smoking or drug handling). Means of seeking to differentiate between drug ingestion and external contamination include:

(i) washing hair samples before testing to remove surface contamination

(ii) analysing the washes

(iii) testing for the presence of the relevant metabolites and establishing the ratio between the parent drug and the metabolite

(iv) setting threshold levels.

(7) Decontamination can produce variable results as it depends upon the decontamination solvent used.

(8) The SoHT has set recommended cut-offs of cocaine and its metabolites in hair to identify use:

(i) cocaine: 0.5 ng/mg

(ii) metabolites BE, AEME, CE and NCOC: 0.05 ng/mg

(9) Cocaine (COC) is metabolized into benzoylecgonine (BE or BZE), norcocaine (NCOC) and, if consumed, together with alcohol (ethanol), cocaethylene (CE). The presence of anydroecgonine methyl ester (AEME) in hair is indicative of the use of crack smoke cocaine.

(10) Cocaine is quickly metabolised in the body: therefore, in the bloodstream the concentration of cocaine is usually lower than that of BE. However, cocaine is incorporated into hair to a greater degree than BE: therefore, the concentration of cocaine in the hair typically exceeds that of BE. Norcocaine is a minor metabolite and its concentration in both blood and hair is usually much lower than either cocaine or BE.

(11) Some metabolites can be produced outside the human body. In particular, cocaine will hydrolyse to BE on exposure to moisture to variable degree, although high levels of BE as a proportion of cocaine would not be expected. It is very unlikely that NCOC will be found in the environment. The fact that cocaine metabolites can be produced outside the body raises the possibility that their presence is due to exposure: this is not the case with cannabis, whose metabolite is produced only inside the body.

(12) Having washed the hair before testing, analysis of the wash sample can allow for comparison with the hair testing results. There have been various studies aimed at creating formulae to assist in differentiating between active use and external contamination. In particular:

(i) Tsanaclis et al. propose that if the ratio of cocaine in the washing to that in the hair is less than 1:10, this indicates drug use.

(ii) Schaffer proposed “correcting” the hair level for cocaine concentration by subtracting five times the level detected in the wash.

The underlying fundamentals are that if external contamination has occurred (and therefore a risk of migration into the hair giving results that would appear to be positive) this is likely to be apparent from the amount of cocaine identified in the wash relative to that extracted from the hair.

An issue in the case was whether the existence of results that showed something, but below the cut-off levels, were evidence of anything

7. Having considered the evidence in this case, I arrive at the same conclusion as Hayden J in Re R, where (at paragraph 50) he preferred “a real engagement with the actual findings” to “a strong insistence on a ‘clear line’ principle of interpretation”. I accept the evidence of the witnesses for the testing companies that when one analyses thousands of tests, patterns can emerge that help when drawing conclusions. It would be artificial to require valid data to be struck from the record because it falls below a cut-off level when it may be significant in the context of other findings. That would elevate useful guidelines into iron rules and, as Dr McKinnon says, increase the number of false negative reports. What can, however, be said is that considerable caution must be used when taking into account results that fall below the cut-off level

The Court gave some practical guidance on the presentation of reports

Report writing and reading

57. The parties have made suggestions as to how the presentation of reports might be developed so as to be most useful to those working in the field of family justice. I will record some of these suggestions and some of my own. Before doing so, I note that each of the testing organisations already produces reports that contain much of the necessary information in one shape or another. It is also important to stress the responsibility for making proper use of scientific evidence falls both on the writer and the reader. The writer must make sure as far as possible that the true significance of the data is explained in a way that reduces the risk of it becoming lost in translation. The reader must take care to understand what is being read, and not jump to a conclusion about drug or alcohol use without understanding the significance of the data and its place in the overall evidence.

58. Comment was made during the evidence that certain courts, and in particular Family Drug and Alcohol Courts, are very familiar with the methodology of hair strand testing and the way in which reports are laid out. The objective must be for all participants in the system, professional and non-professional, to develop a similar competence, even though they do not read as many reports as the FDAC does.

59. There are currently nine accredited hair strand testing organisations working in the family law area. It is not for the court hearing one case to dictate the way reports are written by those who have intervened in this case or by others who have not taken part, but I include the following seven suggestions in case they are helpful.

(1) Use of high/medium/low descriptor:

This is in my view useful, provided it is accompanied by:

· A numerical description of the boundaries between high/medium/low, with an explanation of the manner in which the boundaries are set should be stated.

· A clear statement that the description is of the level of substance found and not of the level of use, though there may a broad correlation.

· A reminder that the finding from the test must always be set alongside other sources of information, particularly where the results are in the low range.

(2) Reporting of data below the cut-off range:

There is currently inconsistency as between organisations on reporting substances detected between the lower limit of detection (LLoD) and the lower limit of quantification (LLoQ), and those between the LLoQ and the cut-off point.

I would suggest that reports record all findings, so that:

· a finding below the LLoQ is described as “detected, but so low that it is not quantifiable”

· A result falling below the cut-off level is given in numerical form

and that this data is accompanied by a clear explanation of the reason for the cut-off point and the need for particular caution in relation to data that falls below it.

(3) Terminology

Efforts to understand the significance of tests are hampered by the lack of a common vocabulary to describe results in the very low ranges, Descriptions such as “positive”, “negative”, “indicates that” and “not detected” can be used and understood vaguely or incorrectly. The creation of a common vocabulary across the industry could only be achieved by a body such as the SoHT. In the absence of uniformity, reporters should define their terms precisely so that they can be accurately understood.

(4) Expressions of probability:

The Family Court works on the civil standard of proof, namely the balance of probabilities. It would therefore help if opinions about testing results could be expressed in that way. For example:

“Taken in isolation, these findings are in my opinion more likely than not to indicate ingestion of [drug].”

“Taken in isolation, these findings are in my opinion more likely than not to indicate that [drug] has not been ingested because….”

“Taken in isolation, these findings are in my opinion more likely to indicate exposure to [drug] than ingestion.”

(5) Where there is reason to believe that environmental contamination may be an issue, this should be fully described, together with an analysis of any factors that may help the reader to distinguish between the possibilities.

(6) The FAQ sheet accompanying the report (which might better be described as “Essential Information”), might be tailored to give information relevant to the particular report, and thereby make it easier to assimilate.

(7) When it is known that testing has been carried out by more than one organisation, the report should explain that the findings may be variable as between organisations.

And I think this line is likely to appear in written submissions from time to time

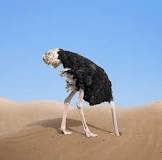

61. The burden of proof is on the local authority, which must prove its allegations on the balance of probabilities. As Ms Markham QC and Miss Tompkins rightly say, the presence of an ostensibly positive hair strand test does not reverse the burden of proof.